Silenced Stories: The Attack on DEI Through School Book Bans

Read more about school book bans and the effect it has on students and the community; specifically how it targets DEI.

Read the full article below or download it here:

Silenced-Stories-The-Attack-on-DEI-Through-School-Book-Bans.docx

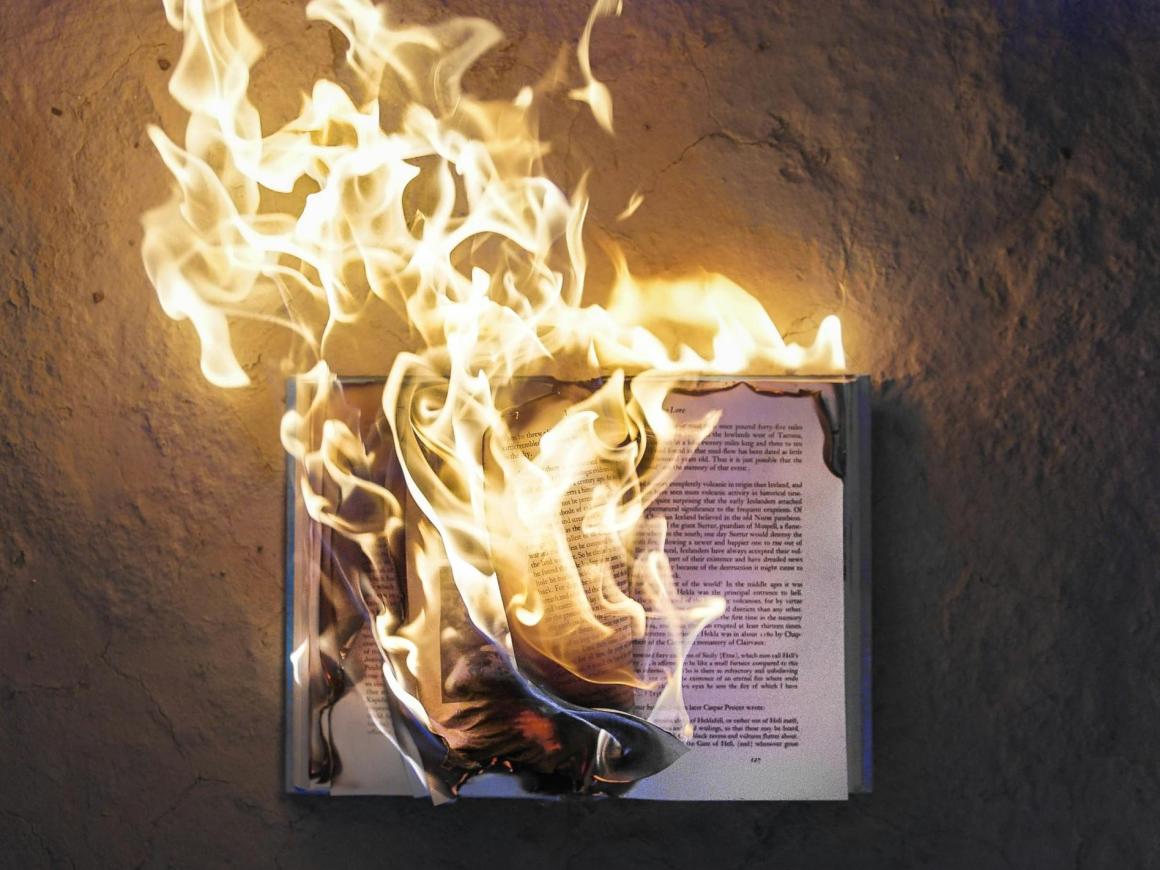

Ray Bradbury, author of Fahrenheit 451, once said, “The problem in our country isn't with books being banned, but with people no longer reading. You don’t have to destroy a culture. Just get people to stop reading them.” This quote illustrates the reason for banning books, and ties to the whole description of what the book is about, taking away education, initially power from the people, by burning books, and making citizens blind to the truth of the government and reality by becoming uneducated. This is very similar to what is currently happening in the U.S. government and around the world, where education rights are being taken away and books are being limited to the people, reinforcing technology as the primary means of learning, as seen in Fahrenheit 451, and only showcasing one side of the story, their own. Book banning remains a highly controversial practice, driven by state laws and school district policies, which suppress academic growth and fuel ideological clashes between parents and the broader public.

Because the U.S. government operates across multiple levels, book banning and censorship primarily occur at the state and local levels. School districts and state officials are at the forefront of deciding whether to ban books. While many books are challenged yearly, not all are successfully banned due to the First Amendment. As the First Amendment Museum explains, “challenging a book is the attempt to ban a book from a library, school district, institution, organization, government entity, retailer, or publisher based on its content.” This concept is particularly relevant to the important Supreme Court case, Board of Education, Island Trees School District No. 26 v. Pico, which examined whether school officials could remove books from libraries based on content. Although this case relates to students’ First Amendment rights, it “failed to set a standard on how to evaluate the motivations of a school district removing books that is applicable outside this case,” which is now the reason why school districts can ban books based on viewpoints (Anderson, 2024). To make this change, federal guidelines are necessary to protect the First Amendment rights of students, yet such reforms seem highly unlikely to happen under the current administration. In a press release titled U.S. Department of Education Ends Biden’s Book Ban Hoax, the Department announced that it will no longer work on cases of book banning, disbanded its “book ban coordinator” role, and dismissed complaints and cases that were already under review (U.S. Department of Education, 2025). The title and language taken suggest a dismissal of the broader impact that book bans may have on students’ access to diverse ideas and learning materials, which shows their lack of support for the needs of schools.

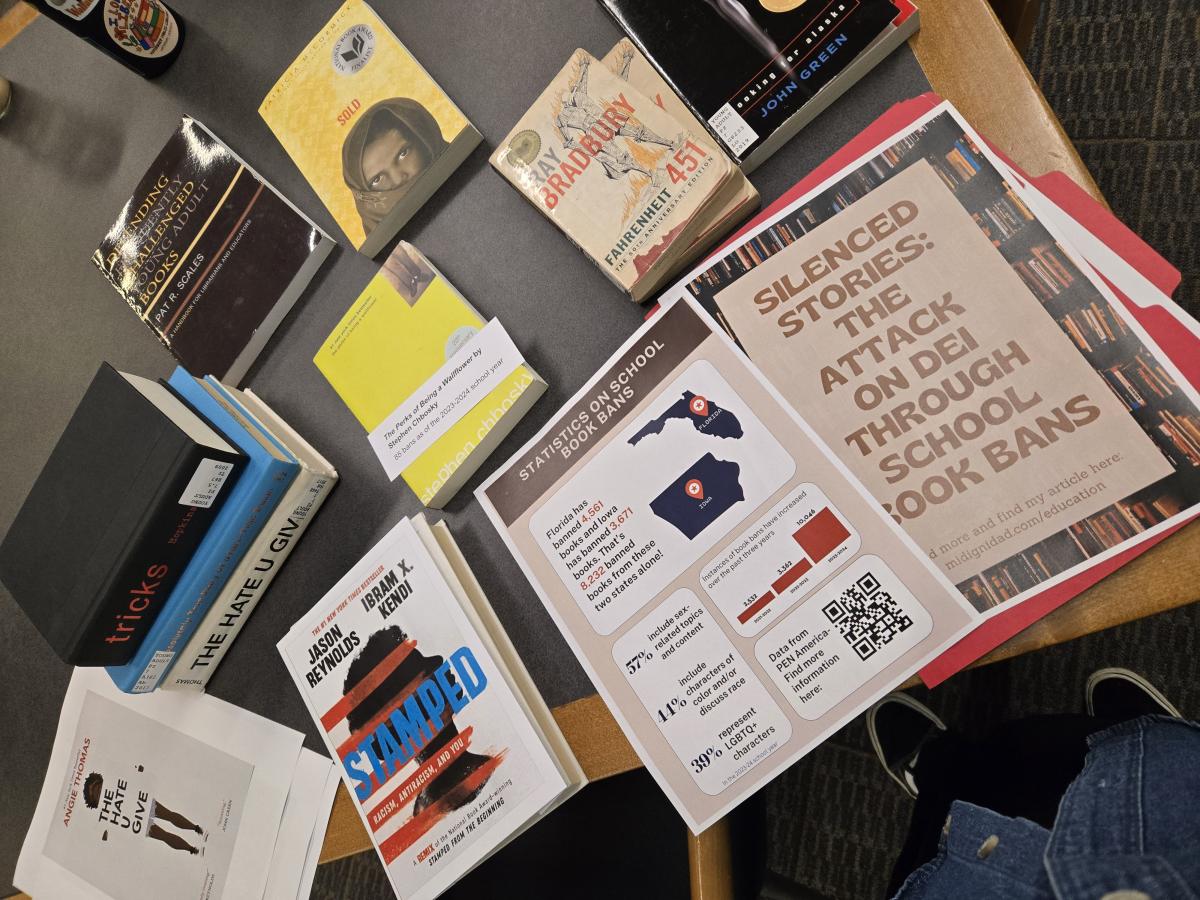

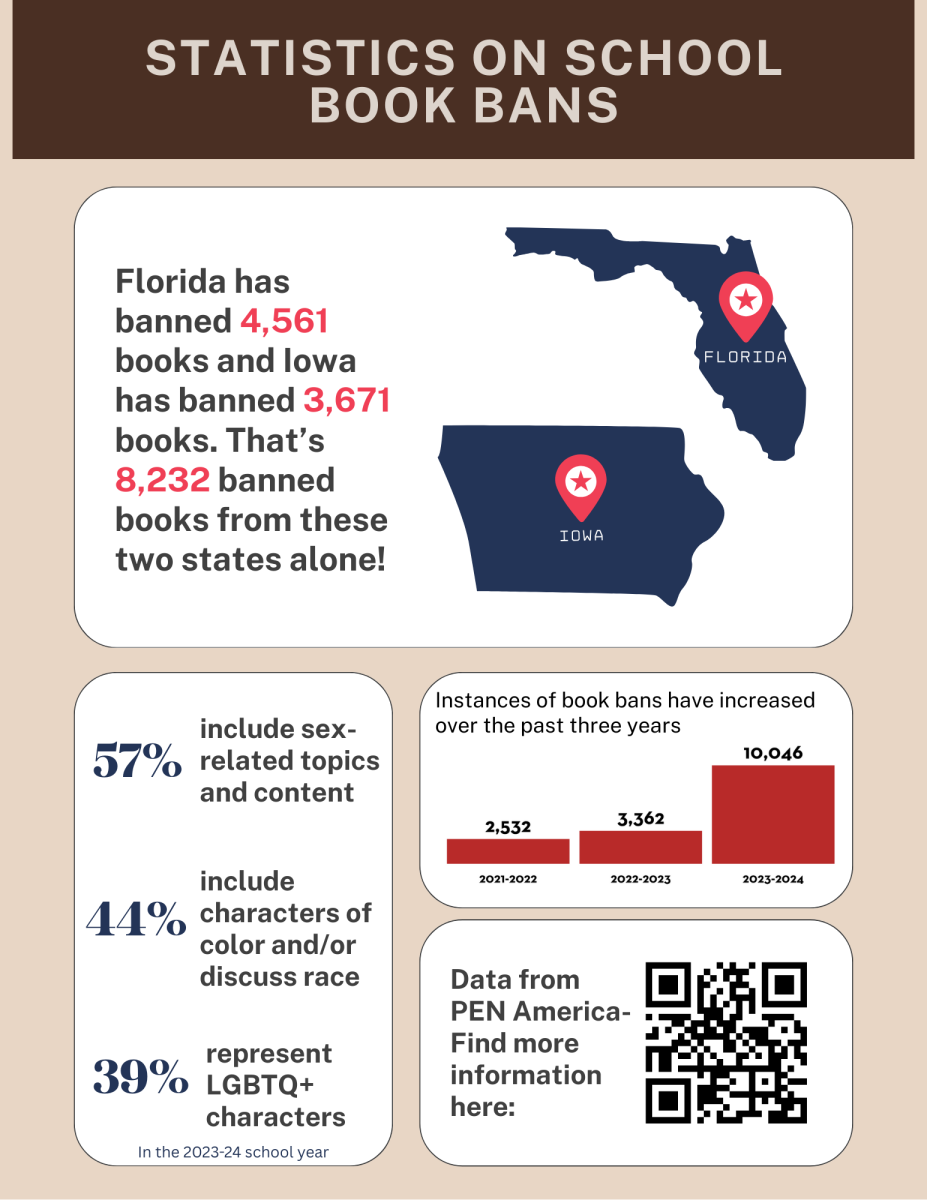

As of the 2023-2024 school year, Florida has one of the highest numbers of banned books, with 4,561 instances; Iowa follows with 3,671 instances (PEN America, 2023). These two states alone have 8,232 books banned. In May 2023, Iowa passed a law, Senate File 496, that requires all materials and school books to be “age-appropriate,” but this prohibits “books with depictions of sex as well as all materials and instruction involving ‘gender identity’ and ‘sexual orientation’ for students through sixth grade.” Fairly after that law came into place, “the Urbandale Community School [in Iowa] has taken what it calls the broadest possible interpretation of the law,” ordering to remove nearly 400 titles from its district libraries and classrooms that were deemed to violate SF496 (PEN America, 2023). Some of these books include The Family Book by Todd Parr, The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas, The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood, and 1984 and Animal Farm by George Orwell, among others (PEN America, 2023). On March 25, 2025, Judge Stephen Locher blocked part of this law after providing a temporary reprieve to publishers who have sued the state for blocking their books in school libraries and classrooms that “depict sex acts.” Locher states, “that the unconstitutional application of the book restrictions ‘far exceed’ the constitutional applications under both legal standards the Court believes are applicable.” (Omaha World-Herald)

As of the 2023-2024 school year, Florida has one of the highest numbers of banned books, with 4,561 instances; Iowa follows with 3,671 instances (PEN America, 2023). These two states alone have 8,232 books banned. In May 2023, Iowa passed a law, Senate File 496, that requires all materials and school books to be “age-appropriate,” but this prohibits “books with depictions of sex as well as all materials and instruction involving ‘gender identity’ and ‘sexual orientation’ for students through sixth grade.” Fairly after that law came into place, “the Urbandale Community School [in Iowa] has taken what it calls the broadest possible interpretation of the law,” ordering to remove nearly 400 titles from its district libraries and classrooms that were deemed to violate SF496 (PEN America, 2023). Some of these books include The Family Book by Todd Parr, The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas, The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood, and 1984 and Animal Farm by George Orwell, among others (PEN America, 2023). On March 25, 2025, Judge Stephen Locher blocked part of this law after providing a temporary reprieve to publishers who have sued the state for blocking their books in school libraries and classrooms that “depict sex acts.” Locher states, “that the unconstitutional application of the book restrictions ‘far exceed’ the constitutional applications under both legal standards the Court believes are applicable.” (Omaha World-Herald)

Although no books are banned in Nebraska, books have been challenged in some districts. In the Papillion La Vista Community Schools (PLCS) policy 6405 states that “The Board deems anything controversial that includes any item from any content area that is an instructional material or library resource that a PLCS parent/guardian/patron asks to be reconsidered for removal from the school program or taught with a different emphasis.”This procedure explains how to handle complaints about controversial educational materials, which are most likely to involve books, and how the principal can support their teachers and meet with the complainant for further discussion. If necessary, the principal can then take the matter to the Assistant Superintendent for Curriculum and Instruction for further review and a meeting with the review committee. An example of this happening was in August 2023, the book All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson was taken for controversial review due to its sexual content and depiction of sexual assault (WOWT, 2023), but the school board rejects the complaint and decides to keep the book in the high school library.

Efforts to ban books in schools are increasingly aimed at undermining Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) by targeting stories and perspectives centered around marginalized communities, especially now with the Trump Administration trying to dismantle and eliminate DEI in schools. There is certainly a theme around the books that are being banned, and it follows silencing racism and the talk about race, sex, and equity.

According to PEN America, as of the 2023-24 school year, 57% of the topics and content [banned] are sex-related, 44% include characters or people of color, and 39% have LGBTQ+ characters or people (2).

These statistics reveal a pattern: rather than protecting students, many bans are motivated by discomfort with inclusive narratives that challenge traditional norms and systemic issues. By disproportionately removing books that reflect racial, gender, and sexual diversity, school districts are limiting students’ exposure to complex social realities and reducing opportunities for empathy, cultural understanding, and critical thinking.

Many students don’t understand the outside world if they have never lived or experienced it; books are these resources to expand their knowledge of the world and grow empathy for others. When I first read Fahrenheit 451 in high school, I didn’t make the connection between this novel and the issue of banning books until now. Many other books I’ve read, like The Hate U Give, I’m Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter, and Rules for Being a Girl, which have all been challenged, have taught me that the world isn’t such a perfect place, especially for women of color, and as women we need to be more vigilant to stay safe. I know this can be a taboo topic and can be the reason parents don’t want their kids to read these types of books, but these books show that you’re not alone and that there are solutions to these problems. It’s better to expose these issues and topics to students to have that conversation now, rather than promoting silence and ignorance, because the issue is never going to go away; it’s how you confront it that makes the difference.

As a future educator, I believe creating a safe space in the classroom involves embracing and accepting students' diverse cultural backgrounds, and what better way to showcase this than with books. Literature that reflects a variety of identities, cultures, and experiences helps students connect to their learning on a deeper level, no matter the grade level, and incorporates that equity aspect. As Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop once said, “All readers must have experiences where they ‘see’ themselves, where they consider different perspectives, and where they are able to ‘step into’ the lived experiences of others.” (Raising Up Antiracist White Racial Justice, 2023). Their essay, “Mirrors, Windows and Sliding Glass Doors,” explains the need for readers to see themselves in books but also have a window to understand and see others. This role of literature promotes both self-awareness and social awareness. When schools remove these books, they erase representation and deprive students of the opportunity to build empathy and engage with diverse viewpoints – both in school and in society. Diversity, as it pertains to DEI (Diversity, Equity, Inclusion), extends beyond race or identifying as BIPOC. People have diverse backgrounds in many ways, such as religion, sexual orientation, disability, socioeconomic status, age, language, and mental health. These facets of diversity contribute to what makes each of us unique. Unfortunately, this understanding is often overlooked in teacher preparation programs. For classrooms to be welcoming and supportive, representation is essential. How can we encourage students to be themselves and feel accepted when books that reflect their identities are being banned?

While state laws and school policies often initiate book bans, much of the momentum behind these efforts is from concerned parents and vocal community groups. Across the country, parents are increasingly challenging books that contain content related to race, gender identity, sexuality, and other topics they perceive as inappropriate or political for schools, when often these concerns stem from personal standpoints and ideological beliefs rather than educational concerns. For example, in Texas, a teacher was terminated from her position after assigning text from Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation after it not being approved and was banned because of parents concerns about it mentioning female and male genitalia, and “as well as potential same-sex attraction,” even when this book is educational for teaching Holocaust history and “its value in demonstrating the plight of Jewish people in Nazy Germany” (Anderson, 2024). This growing influence of parental and public ideology reflects a broader cultural conflict that raises critical questions of authority about who gets to decide what is taught in schools and whose voices are being prioritized or silenced in the process.

The opposition to certain books often comes from parents who do not feel comfortable with their children being exposed to topics like sexuality, gender identity, or profanity that could harm their moral or cultural values. They argue that such materials are inappropriate for school settings and may undermine the values that are taught at home. Although I agree with the point that parents have the right to guide their children's reading, they do not have the right to control and restrict what books are available to others. Parental involvement in education is essential, but recent studies suggest that not all parents support extreme measures like book bans. According to McGehee and Chrastka (2025), many parents express more nuanced views on the issue. Their study on parents' perceptions found that while some parents support limiting access to specific materials, they deem inappropriate, a significant number believe in the importance of maintaining access to diverse literature.

In their research, “67% of respondents felt that book bans infringed on their rights to make decisions for their children, yet 57% of parents said banning books from the school library was an appropriate way to prevent children from learning about certain topics” (McGehee & Chrastka, 2025).

When a single group of parents demands the removal of a book from a library or curriculum, it limits intellectual freedom and robs other families of the opportunity to make their own decisions. Public schools serve diverse communities, and with this, their libraries should do the same, with a wide range of perspectives and experiences.

In our diverse world and community, religion and spiritual ideology play a significant role in our decisions. Public schools, by nature, serve students and families from a wide range of cultural and religious backgrounds, and to be inclusive and equitable for everyone, schools must be inclusive about religion and non-believers as well. This means schools should be open about religion, accepting and celebrating all backgrounds without forcing a dominant religion, such as Christianity in America. As Britannica ProCon points out, banning books on religious grounds can blur the line between church and state, risking the imposition of one group’s belief over others. This tension between personal religious values and the role of public education makes the line for book banning difficult, and the argument of what should/shouldn’t be taught in school since the beginning. Families have the right to practice their religion freely, but this right does not extend to censoring public education for everyone else.

Book bans in various states and school districts disproportionately target literature that addresses diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), particularly works that amplify marginalized voices. These bans, driven more by political and ideological pressures than genuine educational concerns, limit exposure to important real-world issues. Notable examples of banned books include The Diary of Anne Frank, The Handmaid’s Tale, Thirteen Reasons Why, and Animal Farm. Banning these books deprives students of representation and the opportunity to foster empathy. Schools should be safe and inclusive environments, and while parental input is valuable, it should not limit the rights of others to access diverse literature. Protecting the First Amendment and promoting intellectual freedom in education is vital for cultivating open minds and a more equitable society.

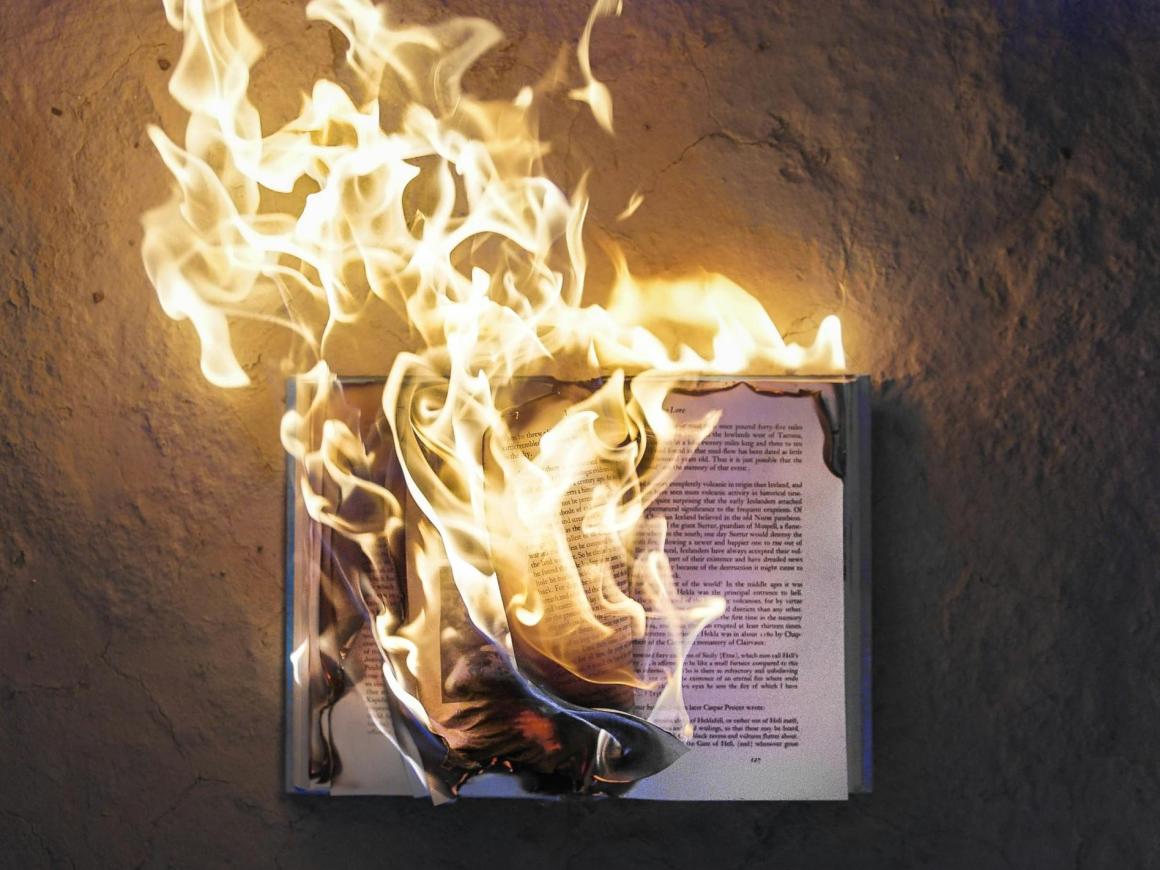

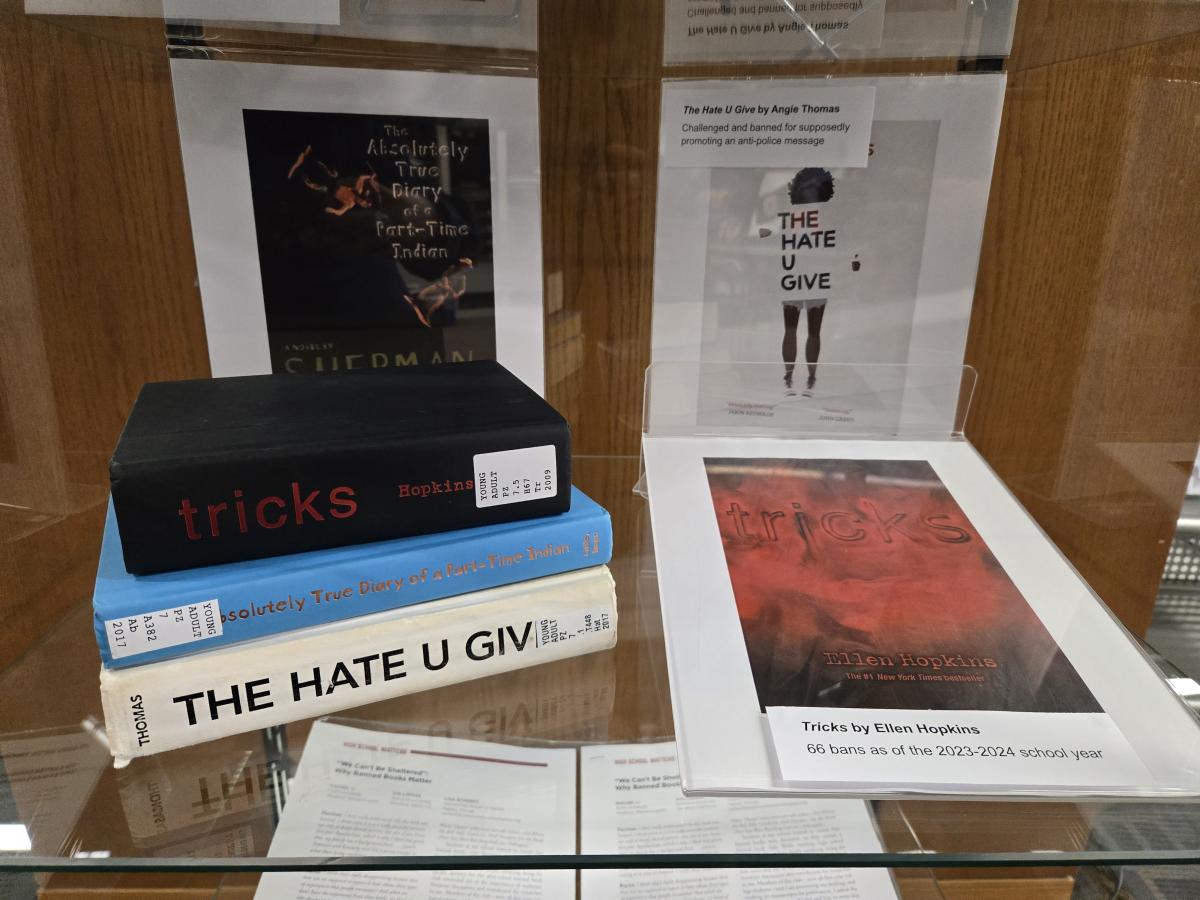

I displayed this article and the banned books I mentioned at my university's library over the summer of 2025! Here are some pictures :)

Works Cited

First Amendment Museum. (2025). How do books get banned? https://firstamendmentmuseum.org/how-do-books-get-banned/

U.S. Department of Education. (2025, January 24). U.S. Department of Education ends Biden’s book ban hoax.https://www.ed.gov/about/news/press-release/us-department-of-education-ends-bidens-book-ban-hoax

PEN America. (November 1, 2024). Banned in the USA: Beyond the Shelves. https://pen.org/report/beyond-the-shelves/

(2025, March 28). Omaha World-Herald (NE), p. 16. Available from NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current: https://infoweb-newsbank-com.leo.lib.unomaha.edu/apps/news/document-view?p=WORLDNEWS&docref=image/v2%3A16E49C67E99CF440%40AWNB-19F99DF28F9A6E1E%402460763-19F99DF9C169C1A0%4015.

PEN America. (2023, August 2). These 450 books are banned in Iowa. https://pen.org/books-banned-in-iowa/

Papillion La Vista Community Schools. (year). 6405 – Controversial Issues.

First Alert 6, WOWT. (Aug. 28, 2023). Papillion-La Vista school board rejects attempt to remove book from library. https://www.wowt.com/2023/08/29/papio-la-vista-school-board-rejects-attempt-remove-book-library/

Raising Up Against Racism, Inc. (2021, December 7). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors – Rudine Sims Bishop. https://ruar.org/blog/mirrors-windows-and-sliding-glass-doors-rudine-sims-bishop

Anderson, R. (2024). Burning Books over Politics: Why Federal Guidance Is Essential to Protect Literature in Public Schools. University of Toledo Law Review, 56(1), 65–86. [PDF] Retrieved from https://research-ebsco-com.leo.lib.unomaha.edu/c/6zkhh2/viewer/pdf/5hile6yg3f

McGehee, M., & Chrastka, J. (2025). Parent Perceptions of Book Bans, Materials Selection, and Reading in School Libraries and Public Libraries. Public Library Quarterly, 1–25. https://doi-org.leo.lib.unomaha.edu/10.1080/01616846.2025.2496591

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. (2025, April 23). Book bans: Pros and cons. Britannica ProCon. https://www.britannica.com/procon/book-bans-debate